What is a balance sheet?

The balance sheet is a financial cornerstone, providing a static snapshot of a company’s financial health at a specific time. As one of the three fundamental financial statements, it is indispensable for financial modeling and accounting. This document serves as a meticulous inventory, detailing a company’s assets—its economic resources—and how these assets are financed, either through borrowed funds (liabilities) or ownership investments (equity). Often referred to as a statement of net worth or financial position, the balance sheet adheres to the fundamental accounting equation: Assets = Liabilities + Equity.

Visually, the balance sheet is divided into two distinct sides. The left-hand side presents a comprehensive list of the company’s assets, categorized into current assets—those easily convertible to cash—and non-current assets, representing long-term investments and resources. Conversely, the right side illuminates the company’s financial obligations (liabilities) and the ownership stake (equity). Liabilities are classified as current, those due within a year, and non-current, representing long-term debts.

The importance of a balance sheet template

The balance sheet is more than just a financial statement, it’s a comprehensive blueprint of a company’s financial architecture. Like a snapshot frozen in time, it reveals the company’s assets, liabilities, and shareholders’ equity at a specific moment. However, its true power lies in its ability to be interwoven with other financial statements, creating a rich tapestry of a company’s overall health. Four critical dimensions of financial performance can be illuminated through the balance sheet

Liquidity

The balance sheet is a reservoir of information about a company’s short-term financial health. By comparing current assets to current liabilities, we can gauge a company’s ability to meet its immediate obligations. Metrics like the current ratio and quick ratio offer precise measurements of this liquidity.

Leverage

The balance sheet is a mirror reflecting a company’s financial risk appetite. By examining the proportion of debt to equity and debt to total capital, we can assess the company’s reliance on borrowed funds. This insight is crucial for understanding the company’s financial stability and potential vulnerability.

Efficiency

While the balance sheet provides a static picture, when combined with the dynamic income statement, it reveals how efficiently a company utilizes its assets. Metrics such as asset turnover ratio unveil how effectively a company converts assets into revenue. Additionally, the working capital cycle offers insights into the company’s cash management prowess.

Profitability

The balance sheet is a cornerstone for calculating key profitability ratios. By comparing net income to shareholders’ equity, we derive a return on equity (ROE), a measure of shareholder returns. Similarly, return on assets (ROA) and return on invested capital (ROIC) provide broader perspectives on the company’s overall profitability and efficiency in capital allocation.

In essence, the balance sheet is a versatile tool that, when used skillfully, can illuminate a company’s financial story from multiple angles, empowering informed decision-making.

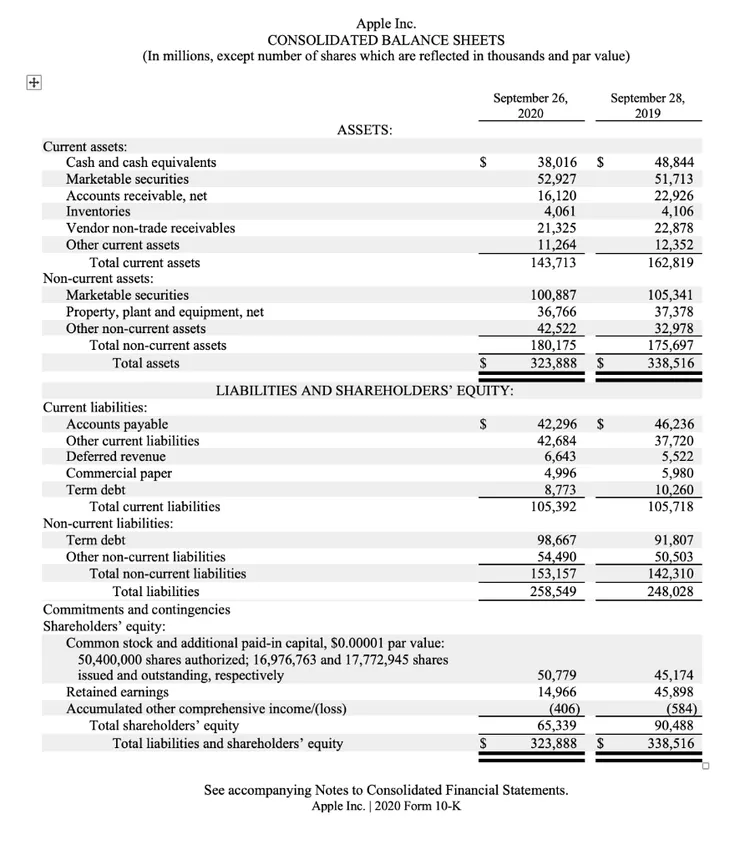

A balance sheet example

The following is a simplified example based on general knowledge of Amazon’s business model. For accurate and detailed financial information, always refer to Apple, Inc.’s official financial statements.

Balance Sheet constituent

A balance sheet is a financial statement that provides a snapshot of a company’s financial health. It comprises three primary components:

Assets

- Current Assets

Cash and Cash Equivalents: The financial heartbeat of a company, cash is the lifeblood that fuels operations. Alongside cash, cash equivalents represent highly liquid assets, such as short-term investments readily convertible into cash. These are the company’s immediate resources to meet short-term obligations, seize opportunities, and weather financial storms.

Accounts Receivable: This asset represents customers’ promises to pay for goods or services already delivered. It’s essentially money owed to the company. While valuable, it’s not immediate cash in hand. Effective management of accounts receivable is crucial to optimize cash flow, as timely collections directly impact the company’s liquidity.

Inventory: This asset encompasses the raw materials, work-in-progress goods, and finished products a company holds for sale. It’s a tangible asset, yet its value is directly tied to sales. Efficient inventory management is vital; excess inventory can tie up capital, while insufficient stock can lead to lost sales. The balance is a delicate one, as inventory levels directly impact the company’s cash flow and profitability.

- Non-current Assets

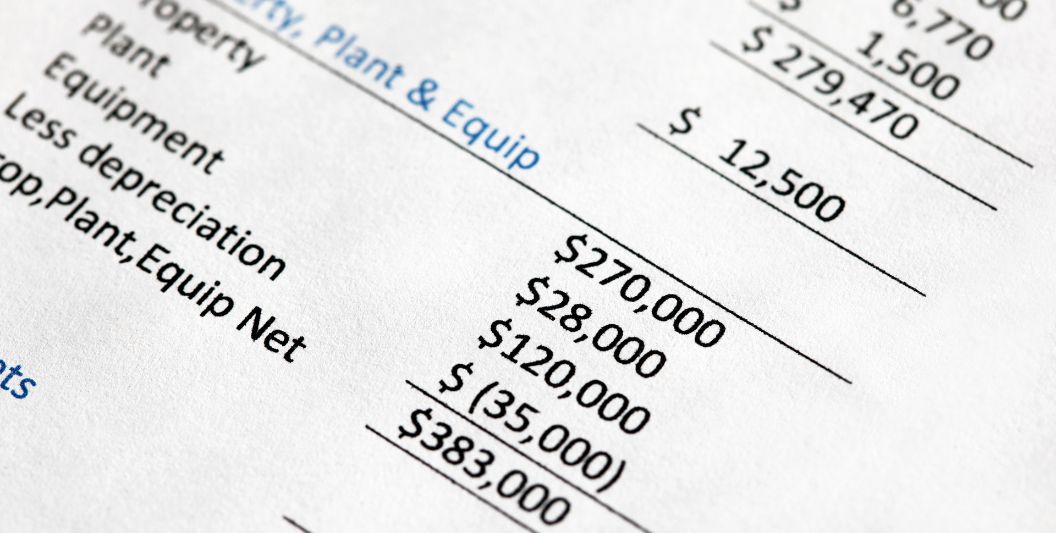

Property, Plant, and Equipment (PP&E): The physical embodiment of a company’s operations, PP&E represents the tangible assets essential for business activities. From factories and office buildings to machinery and vehicles, these assets form the backbone of production and service delivery. However, their value diminishes over time due to wear and tear, technological obsolescence, or economic factors. This depreciation is reflected in the accumulated depreciation account, which is subtracted from the original cost to determine the net book value of PP&E.

Intangible Assets: While often overlooked, intangible assets can be the lifeblood of a company’s competitive advantage. These assets lack physical form but possess significant economic value. Patents, copyrights, and trademarks are prime examples, representing intellectual property that can generate substantial revenue and protect against competition. Additionally, goodwill—the premium paid for acquiring a company above its net asset value—is categorized as an intangible asset, reflecting the value of a company’s reputation, customer relationships, and brand recognition.

These assets are crucial for long-term growth and profitability, but their value is often challenging to quantify and can fluctuate based on market conditions and competitive pressures.

Liabilities

- Current Liabilities

Accounts Payable: This represents the company’s financial commitment to its suppliers for goods or services purchased on credit. Think of it as a short-term loan from suppliers. Effective management of accounts payable is crucial for maintaining good supplier relationships and optimizing cash flow.

Current Debt/Notes Payable: This category encompasses short-term obligations to lenders. Unlike accounts payable, these debts are typically formalized through promissory notes. It’s essentially money borrowed for a specific period, usually less than a year. Timely repayment is essential to avoid default and maintain financial credibility.

Current Portion of Long-Term Debt: While the company may have secured loans with a repayment term extending beyond a year, a portion of that debt becomes due within the current accounting period. This amount is classified as a current liability to accurately reflect the company’s short-term obligations. It’s a financial time bomb that requires careful planning and management to avoid liquidity issues.

- Non-Current Liabilities

Bonds Payable: This represents the company’s formal promise to repay bondholders a specified amount of money at a future date, often with regular interest payments. It’s a long-term debt instrument that the company uses to raise capital. The amortized amount reflects the portion of the bond’s face value that has been allocated to interest expense over time.

Long-Term Debt: This account is a broader category encompassing all long-term financial obligations beyond one year. It’s a catch-all for various debt instruments, such as loans, mortgages, and lease liabilities. Unlike bonds, these debts often have less formal structures and may have varying repayment terms. The debt schedule provides a detailed roadmap of these obligations, outlining interest costs and repayment timelines, and offering a clear picture of the company’s long-term financial commitments.

Shareholders’s Equity

- Share Capital: This represents the cornerstone of ownership in a company. It signifies the funds shareholders have directly invested in exchange for shares. When a company is born, it’s typically these initial investments that fuel its growth. Every dollar invested by shareholders increases both the company’s assets (cash) and its owners’ equity (share capital), maintaining the delicate balance of the balance sheet.

- Retained Earnings: This is the company’s accumulated profits that have been reinvested rather than distributed to shareholders as dividends. It’s a reservoir of earnings that the company can tap into for future growth, investments, or to weather economic storms. Think of it as the company’s internal funding source, strengthening its financial position and independence.

Essentially, shareholders’ equity is the residual claim on the company’s assets after all liabilities have been settled. It’s a reflection of the value built by the company over time through operations and shareholder investments.

How to set up success a balance sheet

Here are detailed steps that can support you in creating a balance sheet exactly

Setting the Stage: The Reporting Date

The first brushstroke in creating a balance sheet is to select a specific point in time. This snapshot date, often the end of a financial quarter or year, serves as the anchor for the entire financial picture. Regular reporting, such as quarterly, offers valuable insights into a company’s financial trajectory. Remember, a balance sheet is a static image of a company’s financial health at a particular moment.

Inventorying the Assets

The next step is to meticulously catalog a company’s possessions—its assets. These are divided into two camps: current assets, expected to be transformed into cash within a year, and long-term assets, which offer value over a longer horizon. Each asset, from cash in the bank to property and equipment, is assigned a value based on its cost or estimated market worth. The total value of these assets represents the company’s resources.

Accounting for Liabilities

Complementary to assets are liabilities, the company’s financial obligations. Like assets, they’re categorized into short-term (due within a year) and long-term debts. From everyday bills to long-term loans, each liability is recorded at its current outstanding amount. The total of these obligations paints a picture of the company’s financial commitments.

Unlocking Equity

With the assets and liabilities tallied, the final piece of the puzzle is equity. This represents the ownership stake in the company. The balance sheet adheres to a fundamental equation: Assets equal Liabilities plus Equity. By subtracting total liabilities from total assets, the company’s equity is determined. A positive equity figure signifies that the company’s assets exceed its debts, a healthy financial position.

The Final Audit

Before unveiling the balance sheet to the world, a thorough review is essential. Every number, every classification, must be scrutinized. Accuracy is paramount. Once confidence in the numbers is established, the balance sheet becomes a powerful tool for understanding the company’s financial standing. It’s a financial blueprint that guides strategic decisions and informs stakeholders about the company’s overall health.

Thank you for reading it at the end and we hope this article about information on setting up a balance sheet. Have an effective working day and stay healthy.